On a chilly January day, the angry mob gathered at the heart of the world’s largest empire on Capitol Hill in front of the capitol building. They were there to protest the injustice done to their populist leader. Thousands of people converged and soon the demonstration escalated. At one point, the enraged crowd advanced through the chain of guards and entered the Senate building. A campaign of destruction and looting of the building began, this is a building full of historical relics in which the nation’s greatest legislators had previously delivered their speeches. The senators, who looked on in amazement at what was happening, apparently could not help but wonder: Is this the end of the Republic? The Roman Republic that is.

It’s Hard to believe, but 2,072 years (almost to the day) before the siege of the American capitol, another Senate building, also on Capitol Hill, in Rome Italy, was attacked by an angry mob. Unlike the attack in the United States, protesters in ancient Rome managed to burn the building to ashes. How did this happen? You ask. Well let me tell you.

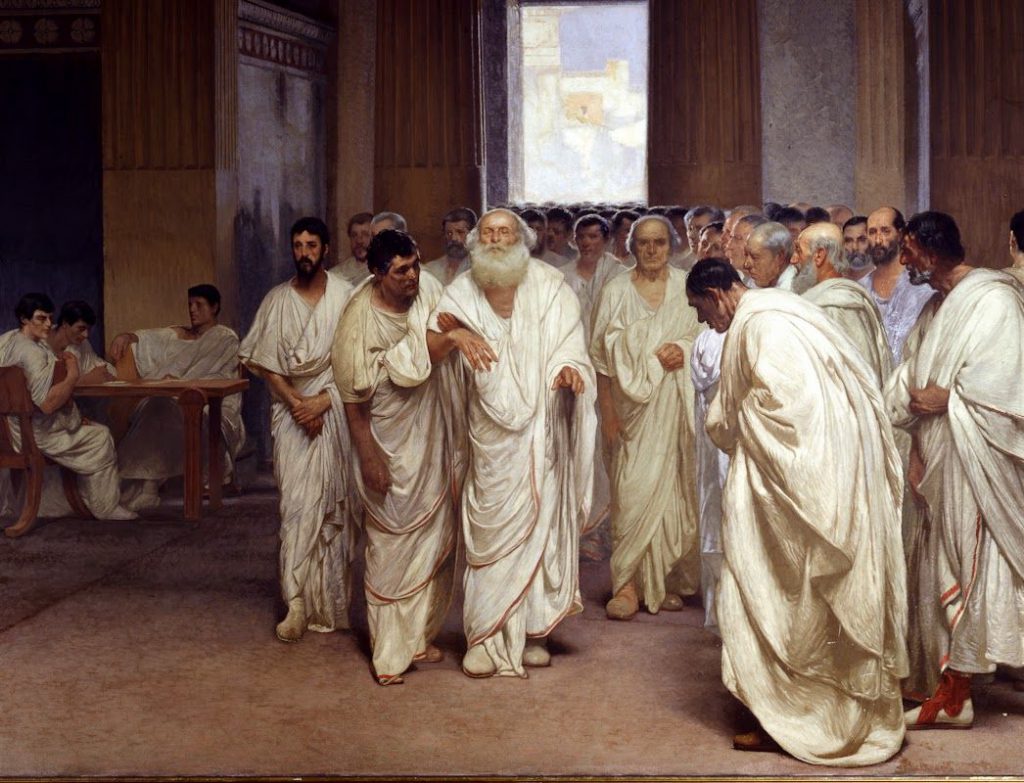

The year is 53 BC and the centuries-old Roman Republic is in its last days. A Triumvirate, a coalition of three central political figures, rules the Roman Empire. The first is Gaius Julius Caesar, he is governing in Gaul and massacring a large part of the population. His partner in the “Triumvirate” Marcus Licinius Crassus has just “lost his head” literally in a failed war campaign in the East. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (AKA Pompeius the Great), the third wing of the partnership, is in Rome, but is preoccupied with political intrigue to overthrow Caesar. This is a period during which the rule of law wavered, and state institutions stopped functioning due to massive use of violence and bribery. In the city of Rome itself a brutal “gang war” takes place between Tios Anios Milo, the candidate for consulate, the most important position in the Roman political hierarchy, and Publius Clodius Pulcher a street agitator and the candidate for Praitura, the second most important role.

Publius Clodius Pulcher was a colorful figure so I’ll dwell on him for just a minute. He was a member of one of the most affluent and distinguished roman patriarchal families – Claudii, whose roots reached as early as the beginning of the republic. Arrogant, smart, hedonistic, unstoppable and with demonstrable contempt for the rules of the game. Clodius did not hesitate to do anything required to make his mark in Roman politics. That’s how, while serving under the command of his brother-in-law, he incited the soldiers to rise up against him, later he had an affair with Caesar’s wife, desecrated holy rites while participating in the “Good Goddess” exclusively female ceremony in a woman’s disguise and reportedly slept with his sister (whose name, in the best Roman tradition was “Claudia”). The Roman people, for their part, followed these deeds in amazement / disgust that can only be compared to watching an episode of the Kardashian family. But behind the hedonistic airs and his privileged approach, there was also a sharp political mind. Thus, Clodius did not hesitate to relinquish his patriarchal status and become a “Plebeian” (commoner) in order to be elected to the tribune (which was open only to Plebeians) in 58 BC. In this position, Clodius initiated extensive populist legislation that included free grain distribution to the people and providing legal validity to guilds, unions of various kinds popular with the common folk. These two laws gained him great popularity and he could use members of the guilds to intimidate his opponents and physically take over the forum and assemblies of the people. Clodius even initiated the exile of Marcus Tullius Cicero, one of the strongest members of the legislature (he went even further and demolished Cicero’s house and took possession of the land for his own house).As a politician, Clodius generally tried to please the members of the Triumvirate and do their bidding, but he was mostly working for himself. When it suited his purposes, Clodius did not hesitate to publicly humiliate Pompey, (“What is the name of the horny commander?” Clodius roared to the crowd in reference to Pompey’s very young wife), and to use guild members to intimidate Pompey until the latter isolated in his own house.

In 52 BC, things exploded with a bang. Clodius’ gangs ruled the streets of Rome and the rule of law was lost. The consuls of 53, who were due to take office in early January, only took office in July. Tios Anios Milo was Pompey’s ally, he adopted Clodius’s cruel bullying methods and set up his own street gangs, which fought Clodius’ gangs. On January 18, 52 BC, in one of the street battles between Milo’s gangs and Clodius’s gang, Clodius was murdered and his body dumped near the shrine of the “Good Goddess” whose rites he had desecrated.

For the masses of common people, who were bedazzled by the high-ranking patrician’s attention and anti-establishment promises, the loss was tragic. Soon the masses began to gather on Capitol Hill. The next day, January 19, 52 BC (almost exactly 2,072 years before the events in the United States), the mob invaded the Senate, instigated by Clodius’s widow, and looted documents, smashed statues, placed the body of their leader on the floor of the Senate and lit a torch. . The Senate House became Clodius’s pyre.

The flames continued to rage, to the cheers of the crowd, and as the Senate collapsed the fire also spread to the first permanent court in Rome. Over time, the Senate structure was rebuilt, more magnificent than ever, however the Senate’s authority and prestige largely went up in flames along with the old structure. Almost three years after Clodius’ death and the burning of the Senate House, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River (on 10 Jan 49) and thus began a civil war that led to the end of the republic (So apparently January is not a good month for the republic …).

Importantly, the burning of the Senate did not constitute the initiation of the fall of the Republic. This is a gradual process that was ongoing for at least a hundred years. The fire did not even constitute the end point of the republic, which continued to poorly perform for several more years. There is no doubt, however, that the burning of the Senate proved the weakness of the Republic and made a real contribution to the “fall of the Roman Republic.”