The Ponary massacre site, 10 km from Vilnius Lithuania, was a popular summer resort for residents of Vilnius prior to World War 2. In 1940, the Soviet authorities controlled the area and dug out huge pits for fuel tank disposal. The tanks were never buried in these pits. Instead in 1941, after conquering Vilnius, the Germans turned Ponary into a mass murder site. About 100,000 people were killed in the Ponary murder pits, including 70,000 Jews.

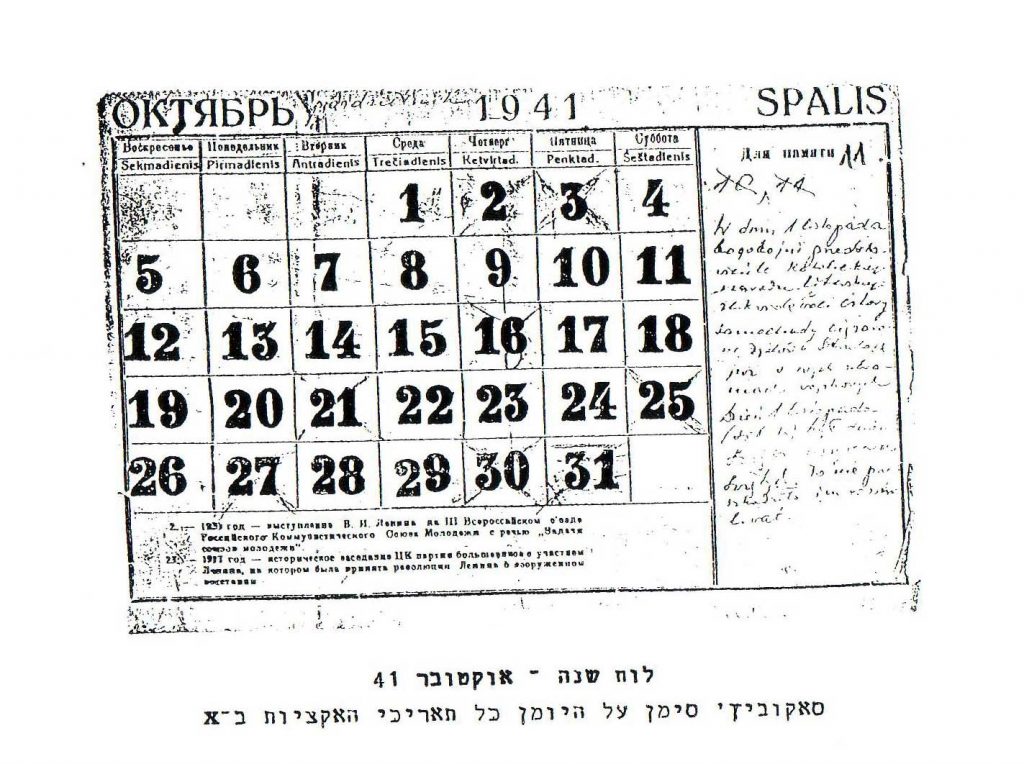

A Polish journalist named Kazimierz Sakowicz (1899-1944) who lived in Ponary, in a house close to one of the shooting pits, witnessed and documented daily what he saw and heard. Sakowitz began documenting what he witnessed in July 11, 1941, on the 19th day of the German occupation. From that day onwards, he documented all the horrific events in Ponary without fail. His last entry was November 6, 1943. A total of 835 days of genocide were documented in great detail. He used any writing materials he had including old papers and used calendars. He stashed them in glass bottled which he buried in his backyard. After the war the bottles were discovered.

Sakowicz ‘s diary – despite being the only comprehensive witness document available, detailing the daily occurrences of the mass murder in the Ponary massacre site, – has largely gone unnoticed. For decades the diary was hidden in the archives of the Historical Department of Lithuania. The Lithuanian authorities were eager to hide it from the public eye, especially because it is a clear indication of Lithuanians direct cooperation and participation in the murders. The late Dr. Rachel Margolis, a survivor of the Vilnius (Vilna) Jewish community, who served as deputy historical director of the Vilnius Holocaust Museum after the war, discovered and revealed the diary. For years Margolis worked on reconstructing and deciphering the discovered diary. Margolis wrote:

“While searching for documents in the Central Lithuanian State Archive, I discovered a folder with a number of handwritten yellowing pages. Some of them were simple papers from 5 to 25 cm long, others were margins of a Russian-Polish calendar of 1941. The records seem to have been written in great haste, with a trembling hand. On many pages an “unreadable” stamp was stamped by the archive. That was my first glimpse of the Sakowicz diary. Under special light and using a magnifying glass, I was finally able to sort it and read.”

It was only in 2005, 64 years after Sakowicz first began documenting the Ponary events, that the diary was published in English by Yad Vashem and Yale University Press in the United States. In its introduction, editor Dr. Yitzhak Arad wrote “Sakowicz’s diary is unique. No similar documentation has survived from any of the other mass murder sites at which Jews were shot: Babi Yar in Kiev, Maly Trostinets near Minsk, Bogdanovka in Transnistria, and hundreds of other places in the occupied Soviet Union”.

Analysis of the diary reveals significant information about the murders in Ponary, including information that was previously unknown. The diary shows extensive cooperation on the part of the local Polish and Lithuanian population. Logistical assistance provided close to the murder sites such as: providing accommodations, supplying of food and alcohol to the murderers, postal and transportation services, and direct participation of Poles and Lithuanians, residents of Ponary and the surrounding area, in the trade of the victims’ property personal effects. In this regard, Sakowitz writes:

“There is a close connection in Ponary between the Lithuanian railway workers, the Lithuanian police and the girls working at the Ponary post office, Ponary became a Lithuanian colony…”From the 14th July 1941, the jews are undressed and the trade in their clothes is flourishing. Every day, carts arrive from the village of Gorla and stop at the guard station (Gardinska), where a clothing trade center has been established. From here the clothes of the murdered are taken in sacks, and sold. A suit is sold 100 Rubles, and you can find additional 500 Rubles sewn inside. For the Lithuanians, 300 Jews are 300 pairs of shoes, pants and clothes. ” “Everyone is waiting for more victims.”

Above all, Sakowitz reveals the Lithuanians’ direct participation in the extermination apparatus. Throughout the documentation the Lithuanians are mentioned as the main perpetrators of the murders. Sakowicz calls the Lithuanian assassins – the Shaulis (Lithuanians carrying weapons or “ponry guns”). The diary indicates that the Germans were mainly involved in planning, supervision and administration, while the shooters and perpetrators were mainly Lithuanians. In modern era we are told that the Nazis were the cruel perpeterators and the local residents only their accomplices. Sakowitz states otherwise. He describes the inconceivable cruelty of the Lithuanians when he writes about the horrific abuse they inflicted on their victims before their murder.

“The Jews who undressed slowly were beaten by the Lithuanians with batons to their heads. People sought refuge and ran into the pit. The shots were plentiful. One woman, all smeared with blood and dressed in white, was hit by the butt of a rifle. The woman fell, and was thrown in the pit without being shot. Another woman stood with a baby in her arms and two little girls grabbing at her dress, the Lithuanian snatched the baby from its mother and threw him into the pit. The woman, mad with grief and pain, ran after the baby to the pit, and with her two little girls. Three shots followed”

Three days before his diary was completed on 3rd November 1943 he wrote:

“Again a car arrived with Jews, most of them women and children. The victims were stripped in the car and thrown naked into the pit. The Lithuanians shot them from above like birds. A barrel of chlorine is now standing next to the pit. They throw in the chlorine without bothering to eliminate them. ”

Sakowitz’s diary provides a new light on the events of those years and serves as a unique analytical tool in understanding and documenting the first stage in the final solution – the massacres in the shooting pits. Sakowitz’s simple and objective documentation, allows the conventional study of these extreme and exceptionally traumatic events, which the historian himself finds difficult to document and investigate. The events are presented indirectly and allow both the reader and the investigating historian an in-depth understanding of the killing process.

For the past three years, the author of these lines has been investigating the diary and murder events in Ponary.